Koalas may seem adorable at first glance, but they hide a scary secret: chlamydia – the most common sexually transmitted disease in humans.

The first sign is the smell – it smells like a fire mixed with urine. The second sign is the koala’s hindquarters – it is inflamed and wet, with brown streaks. That’s when you know the koala is in trouble.

Jo – the animal lying curled up on the operating table – has both of these symptoms.

The key to developing vaccines for humans

Jo is a wild koala being examined at Endeavor Bio-Veterinary Center, a unit specializing in treating diseased koalas in Australia. Doctors discovered that the last two times they saw it in the forest, Jo showed signs of illness.

So they took him and his 1-year-old baby to the facility’s main clinic – located in a remote bushland in Toorbul, north of Brisbane – for a comprehensive check-up.

With the naked eye, veterinary expert Pip McKay immediately recognized what Jo’s problem was.

“Looking at it, it probably has chlamydia,” she said.

Humans are not the only animals that get sexually transmitted diseases. Oysters can get herpes, rabbits can get syphilis, dolphins can get genital warts, and chlamydia – a single-celled bacteria that acts like a virus – has succeeded in infecting everything from frogs and fish to macaws, humans and even koalas.

This ubiquity of chlamydia has led some scientists to suggest that koala research and conservation could be the key to developing a lasting cure for the common sexually transmitted disease. especially in humans.

“They (koalas) are out there, they have chlamydia and if we can give them a vaccine we can observe the actual effectiveness of this vaccine,” said Peter Timms, a microbiologist at the University of California. studying Sunshine Coast in the state of Queensland, commented.

Mr Timms has spent the past decade developing a chlamydia vaccine in koalas, and is currently testing it on wild koalas, hoping that his formula will soon be used more widely.

“You can test things on koalas that you can’t do on humans,” Mr. Timms explained.

Unlike humans, chlamydia causes extremely serious damage to koalas, they can become blind, infertile and die after infection. The type of bacteria that causes disease in koalas is still quite similar to the type that causes disease in humans, because in fact chlamydia bacteria only has 900 active genes, much less than other infectious bacteria.

Because of these similarities, the koala chlamydia vaccine trials that Dr. Timms and Endeavor are testing could provide valuable clues to global researchers developing human vaccines.

The disease is common in both humans and koalas

With 131 million new infections detected each year, chlamydia is the most common sexually transmitted disease in the world. One in 10 teenagers in the US is infected with the disease, according to Dr. Toni Darville, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina.

Antibiotics can fight the disease, but that is not enough because, according to Dr. Darville, chlamydia is a “stealth organism”, causing few symptoms and often remaining undetected for many years.

“We can detect infected people and treat them, but if you don’t treat their sexual partners, you only need one spring break season for people to get infected again. They can get vaginal infections.” “Stay for a long time without even knowing about it. When they turn 28 and are ready to have children, they discover everything is a mess,” said Dr. Darville.

In 2019, Dr. Darville and her colleagues received a $10.7 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to develop a vaccine. Ideally, a vaccine for chlamydia and gonorrhea would be combined with the vaccine being used to prevent HPV infection, which is being given to children and adolescents.

“If we combine all three, we will essentially have a vaccine to prevent reproductive cancers,” Ms. Darville said.

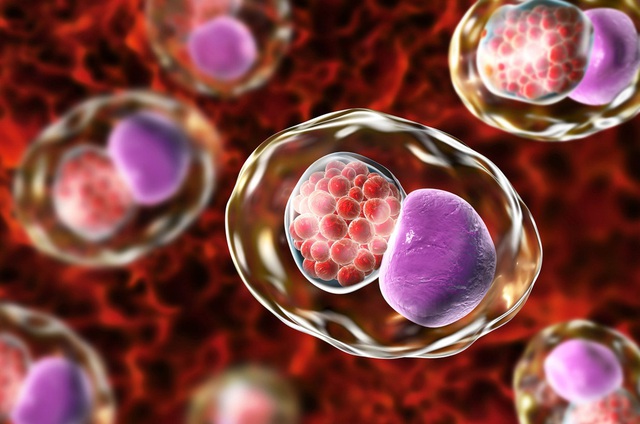

Chlamydia is a sneaky bacteria, and it is divided into two stages when it enters the human body. It starts out as a basic structure, sneaking into cells and hiding from the body’s immune system. After entering the cell wall, it forms a covering membrane, takes control of the host cell and begins to release copies of itself. These copies either exit the cell or are released into the blood to continue their journey to other places in the body.

“Chlamydia is quite unique. It has evolved to survive extremely well in a specific niche environment, does not kill the host and only causes real effects after a long period of time,” said Mr. Ken Beagley, professor in immunology at Queensland University of Technology, explains.

Bacteria can survive in the genital tract for months or years, damaging the reproductive system. Scarring and chronic inflammation can lead to infertility, ectopic pregnancy or pelvic inflammatory disease. Evidence shows that chlamydia also harms male fertility.

Researchers found there are strong similarities between chlamydia bacteria in humans and in koalas. The only difference is severity; in koalas, the bacteria quickly travel up the urethra and can jump from the reproductive organs to the bladder.

These similarities have led Dr. Timms to suggest that koalas could serve as the “missing link” in the search for a chlamydia vaccine that works in humans.

“Koalas are not just a fancy animal. They are actually very useful in studying humans,” said Mr. Timms.